Interview with Mike Shanahan

The first interview of the year is with author Mike Shanahan, another talented Unbounder. Thanks for joining us, Mike! 1) To start with, could you introduce yourself and tell us about your current project?

Hi. My name is Mike Shanahan and I’m a freelance writer and editor.

What occupies me now, outside of ‘real work’, is my new book about how fig trees have shaped the story of humanity and, thanks to their bizarre biology, could help us address some of the big challenges facing our planet.

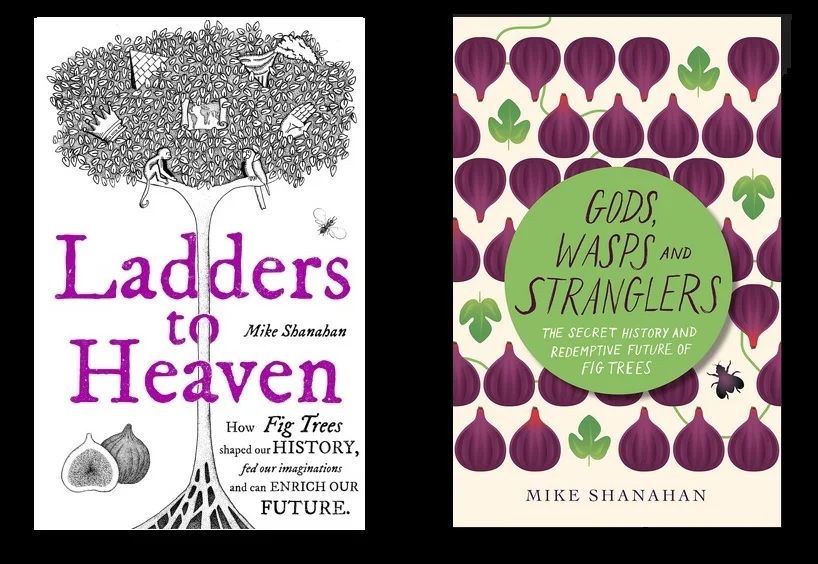

The book has different titles in the UK (Ladders to Heaven) and the US/Canada (Gods, Wasps and Stranglers).

Here’s its liner summary:

Fig trees fed our pre-human ancestors, influenced diverse cultures and played key roles in the dawn of civilisation. They feature in every major religion, starring alongside Adam and Eve, Krishna and Buddha, Jesus and Muhammad. This is no coincidence – fig trees are special. They evolved when giant dinosaurs still roamed and have been shaping our world ever since.

These trees intrigued Aristotle and amazed Alexander the Great. They were instrumental in Kenya’s struggle for independence and helped restore life after Krakatoa’s catastrophic eruption. Egypt’s Pharaohs hoped to meet fig trees in the afterlife and Queen Elizabeth II was asleep in one when she ascended the throne.

It’s all because 80 million years ago these trees cut a curious deal with some tiny wasps. Thanks to this deal, figs sustain more species of birds and mammals than any other trees, making them vital to rainforests. In a time of falling trees and rising temperatures, their story offers hope.

Ultimately, it’s a story about humanity’s relationship with nature. The story of the fig trees stretches back tens of millions of years, but it is as relevant to our future as it is to our past.

2) Would you mind sharing an excerpt with us, or a favourite quote?

Here’s the opening of Chapter 6: ‘Sex and Violence in the Hanging Gardens’.

On a moonlit night in southern Africa, a reproductive race is about to begin. The stakes are high but so are the risks. Most of the competitors will be dead or doomed by dawn. The starting line is a solitary fig tree whose gnarled form towers over a small stream. Figs hang in clumps from its branches like a plague of green boils. Tonight they erupt with life.

An insect emerges from a hole in one of the figs. She’s so small you could swallow her and not notice. She’s a fig-wasp with an urgent mission and her time is running out. All around her, thousands of her kind are crawling out of figs. Each one is a female with the same quest, and each faces immediate danger. Ants patrol the figs, and they show no mercy. Their huge jaws will crush and dismember any fig-wasp that delays her maiden flight.

Our fig-wasp avoids this fate with a flap of her wings that lifts her clear of the carnage. She carries inside her body a precious cargo, hundreds of fertilised eggs that she can lay only in a fig on another tree. But she is fussy. The fig she seeks must be from the right species of Ficus, and it must be at the right stage of development. If it is ripe, she will be too late. If it is too small, the fig will not let her enter. The nearest fig that fits the bill could be tens of kilometres away.

The wasp does not have time on her side. With every minute that passes her energy stores deplete and can never rise again, for in her short adult life she never once eats. She has less than 48 hours to complete her mission, and although she has left the ants behind, the air brings fresh danger.

Out of the dark night swoop bats, their mouths agape, their stomachs empty and expectant. The bats fly looping sorties through the clouds of dispersing wasps, condemning those they swallow to an early death. Our wasp escapes only when a gust of wind blows her high into the sky. She has eluded the predators. Now she must face the elements.

3) What inspired you to write this book?

I fell into the story in the late 1990s when I lived in a rainforest national park in Borneo where I was studying wild fig species for my PhD. I left academia but wherever I went after that I came across stories about how fig trees had influenced diverse cultures around the world. The more I researched, the more these trees amazed me. I believe everyone should know their story, because it is also our story.

4) What’s your next project?

I wrote a children’s book 15 years ago. When I can face it, I will be rewriting it from start to finish. Who knows… in another 15 years it might be finished.

5) What does your typical day look like?

From 6am until 8.30am most days I’m taking care of my son and getting him to nursery school. Then I have quick stop at a local cafe for caffeine and half an hour of ‘writing’. This can include anything from reading for research to working on plot structure, or editing yesterday’s work.

From 9am until 5pm, I’m working from home in my day job, writing and editing for various clients. Most of my work relates to rainforests, climate change and biodiversity. I spend the day at my laptop so try to squeeze in a bit of my own writing time, but most days don’t succeed. If I can, I like to get out of the house and spend some time writing in a café in town.

The next few hours are all about parenting and cooking and conversation, maybe some writing, maybe some good TV.

6) What’s the most important think you hope people will take from this book?

That we are part of nature, not apart from it. That our wellbeing depends on that of the environment. And that we are new here and need to grow up fast.

7) Which part of the writing process is your favourite, and which part do you dread?

I like the technical-cum-creative challenges writing throws up — like the challenge of writing good transitions between scenes or themes, and the challenge of subtly threading elements of a theme throughout the whole book. To me these are all like puzzles. I enjoy the challenge and satisfaction of solving them. I like the research too. I tend to fall down rabbit holes and enjoy knowing that they can lead to either dead ends or new caverns of wonder.

There’s nothing I really dread about writing. One of the hardest parts of writing my new book, was that I was also editing as I wrote. I would make a change in one part of it and it would have implications for text in other chapters. So I ended up going round in circles for a while. The problem was that I hadn’t settled on my overall structure. When I did, the writing-editing suddenly became so much easier.

8) What is your number one distraction?

Twitter, without a doubt.

9) How do you approach research? Do you have notes for the whole book in advance or research a section at a time?

I did a lot of research for my new book. In the end, I used more than 340 published sources, mostly books and research papers in academic journals.

To keep track of new information, I set up Google Alerts for relevant words and got an email any time they were mentioned in news articles, scientific papers, blogs and anywhere else on the internet. I kept this up for several years. By casting this huge net I caught some great ideas.

I wrote and researched at the same time. I had one huge ‘Notes’ document where I chucked everything I came across. As I wrote, I used the endnote function in Word to keep track of information sources or leave notes to myself about particular sentences and blocks of text. It was pretty messy but it worked. Next time, though, I want to be less chaotic.

10) Tea or coffee?

Tea first thing. Coffee for the rest of the day.

11) What are the most important three things you've learned about writing, editing or publishing (or all of the above!) since you started your journey?

Writing: I learned the importance of planning, of plotting out narrative structure and having a good sense of where I want the words to take the reader. I wasted a lot of time and energy writing words that I would never end up using.

Editing: I learned I love editing. Patience helps. Sometimes I could spend two hours on a sentence. Other times, I made wholesale changes very quickly – moving many large blocks of text to new chapters, or moving whole chapters and changing the entire shape of the narrative. I started adding the word ‘machete’ to my file names after particularly brutal chopping and changing. I was on my 80th draft when I at last started to feel satisfied with it.

12) What's your favourite quote on writing?

Peter Cook: I met a man at a party. He said ‘I'm writing a novel’. I said ‘Oh really? Neither am I’.

13) What is the best piece of advice you've received?

Something that has stuck with me is science writer Tim Radford’s advice that the point of writing is to have somebody read it. He says: “So the first sentence you write will be the most important sentence in your life, and so will the second, and the third. This is because, although you – an employee, an apostle or an apologist – may feel obliged to write, nobody has ever felt obliged to read.”

Radford suggests placing by the keyboard a little sign that says "Nobody has to read this crap." I didn’t make a little sign, but I always remember that phrase when I am writing.

14) Where else can we connect with you?

You can find me on Twitter (@shanahanmike) or at my blog — Under the Banyan